The Five Thousand-Meter Fantasy

People never seem to tire of the Noah myth. It has it all: the hopeless depravity of mankind (always a popular theme) complemented by the contrasting goodness of Noah complete with flowing white locks and beard; the "I'm-fed-up-with-all-this-fornicating" pronouncement from God; the mighty cubit-stretching labor on the big round boat; then the parade of all those darling animal couples, plus the Flood itself. And ending it all, we get not a bang, not a whimper, but a wonderfully satisfying crunch as the Ark comes to rest on "Mt. Ararat," after which the survivors get to go forth, procreate, and become sinful all over again.

There must be something magical about this tale; why else would so many people spend so many years searching, wrinkling their brows, and stroking their chins in perplexity over the "Legend of the Lost Ark," the "Mysteries of the Great Ararat," or whatever. Other traditions, Jewish and Islamic, also tell Noah's story, but only American Christians, it seems, are so keen on it that, every few years, some well-heeled evangelical businessman (or, once, an ex-astronaut) will open up his wallet and mount a pseudo-scientific expedition to that heap of Kurdo-Armenian rock known as "Mt Ararat." The Ark enthusiasts never quit. They are, after all, not that far theologically from the people who find Jesus on the scorched exteriors of carbohydrates. They have seen--they say--images of the Ark in aerial photographs. They've analyzed fragments of wood. They've done carbon-dating and spectography. They've puzzled and pondered and pretty much done everything they could to find an answer. They are, dare I say it, just a little bit of cuckoo. As Dave Barry has noted, there is a very fine line between the words "hobby" and "mental illness."

The shares of Cuckoo Inc., however, are always in a bull market, and the Noah business will never go out of style. Readers who want to confirm this can find a nicely-done history of Ark searches at Wikipedia. My favorites (of course) are the hoaxers, especially George Jammal, a guy in California whose splinter from the Ark turned out to be wood he found on a rail-bed, then aged at home in his oven using various sauces. The image this evokes, that of museum graybeards closely inspecting the artifact, wondering why it would smell faintly of teriyaki, never fails to brighten my day. If, however, you're educated (i.e., an elitist liberal humanist snob), you know that the Genesis flood myth is just one of many in the world, the most famous being that of Gilgamesh. And you know that the "Mt. Ararat" of eastern Turkey has nothing to do with a Mesopotamian flood story. That, and the "Real Honest-to-God Landing Place," are what this piece is all about.

First, let me assure you: it will not be extensive. All I have is a few pictures of the Genuine Article--one taken by a dead Englishwoman, two others by Kurdish outlaws. What "Genuine Article"? A fair question. To answer it, I'll start off by raiding my own cupboard. The following passage is taken from the Notes (p.336) at the end of Fever and Thirst:

Here it must be said that few knowledgeable travelers take seriously the claims of "Mt. Ararat" in Turkey to be the resting place of Noah's Ark. In the Middle East, only the Armenians regard the "mountains of Ararat" (Genesis 8:4) to be this particular peak. The name "Ararat" in the Old Testament clearly denotes a country or geographical area, not a specific mountain, and the three A's in the name are an important indicator. During the early Christian era, when scholars were trying to translate Biblical texts in Aramaic, which does not have vowels, into Byzantine Greek, which does, they ran into problems with unknown words. When dealing with the story of Noah's Ark, they came upon a name they did not recognize: a place denoted by the symbols for -R-R-T. In the absence of a clear answer, they gave up and inserted -A- in the three slots indicated. Thus "Ararat" was produced. We now know this ancient country by its more accurate name: Urartu, a kingdom centered upon Lake Van which was a rival to Assyria. Thus, an accurate translation of Genesis would say that Noah's Ark landed on the "mountains of Urartu," which is no more specific than saying "the mountains of Switzerland." (Additional note: the Peshitta, the ancient version of the Bible used by the East Syrian Church, states that Noah's Ark landed on the "Turé Kardu"; i.e., the mountains of the Kurds.)

But, you may object, the mountain in question is still called "Ararat." Why is it called that if it isn't the right one? Because that isn't the mountain's correct name. In fact, it was a European, William of Rubruck, who first stuck that label on it in the 13th century A.D., and it was Europeans thereafter who perpetuated the mistake. The Armenians, then and now, called it Massis, even though, after they became the first officially Christian nation, in 301 A.D., they adopted this imposing peak as the landing-place of Noah. Still, to them it is Massis. This is why, when you drive the streets of south Glendale, California, through the largest concentration of Armenians in the U.S., you see signs on the storefronts saying things like "Massis Laundry," "Massis Bakery," or "Massis Armenian Grocery." A mountain as imposing as this one (photo above) needs no Ark legend to justify its status as a national symbol.

Gertrude Bell (1868-1926) was far too intelligent to take the King James Version at face value. In the spring of 1909 the great explorer found herself at Judi Dagh (Cudi Dagi) near the town of Cizre, just east of the Tigris in southeast Turkey. On 14 May she wrote to her mother in County Durham:

On the first [day here at Judi Dagh] I climbed up into the hills and saw a very ancient fortress on a crag - Assyrian I suspect for there was an Assyrian stele below it. My guides were the Protestant priest, Kas Mattai, and his brother Shim'an...I walked through the oak woods on the mountain sides all the morning with Kas Mattai and it was so wonderfully beautiful that I determined to have another day of it and go to a summit.

Even in May, the Tigris valley heat is merciless, and Miss Bell could not resist the idea of making for the summit:

So yesterday we set off at 4 and climbed through the oak woods for 2 hours and then we came out onto the mountain tops where the snow was still lying in great wreaths and the high mountain flowers were in bloom. There were few of the real alpines - perhaps I wasn't high enough up for them - but the great beauty was the bulbs.

Gertrude Bell was English, and like any English writer worthy of the name she could not resist a thorough (and tedious) identification of every flower that she encountered. At last, however:

But I forgot to tell you what it was I came out to see - I wasn't just taking the air in the mountains, I went up to look at - the Ark.

That's right: the Ark. She had climbed up Judi Dagh to find "Noah's Ark." Gertrude, in her rambling way, goes on to explain:

There is a large body of opinion in favour of this [Judi Dagh] having been the place where it alighted and I also belong to this school of thought partly because, you see, I have seen the Ark there and partly because, since the Flood legends are Babylonian, it's far more likely that they chose for their mountain the first high mountain that they knew (which is this Judi Dagh) rather than a place far away in remote Armenia.

Right. In other words, the people who set down these legends lived in the plains of Mesopotamia. The present-day "Mt Ararat" of eastern Turkey was located far away from any that they knew. They did, however, know those sizable ranges which hemmed in the north reaches of the Tigris. And the first and most visible of these was Judi Dagh, Mt. Judi, crowding in against the left bank of the great river. That is why, of the ancient sources, one (the Koran) specifically identifies Judi as the landing place of the Ark, and two others call it "the mountains of the Kardu" and "the mountains of Urartu," which amounts to the same thing.

We got up to the Ark about 9 - it was a most wonderful place from which you could see the whole world, though I must confess there isn't much of the Ark left.

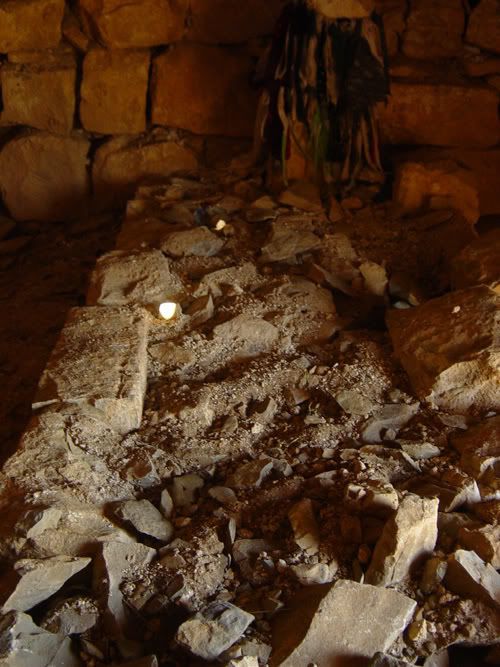

An understatement, as we can see from Miss Bell's photograph (above). Obviously this is not the Ark per se, merely a ziyaret, a place of pilgrimage, for those who come to pay homage to Nebi Nuh, the Prophet Noah. It was periodically used as a monastery for solitary anchorites who came to read the Scriptures and meditate. By Gertrude Bell's time it was abandoned and open to the sky. Until modern times, accounts tell us, this was the place where people of the three monotheistic faiths, Christian, Muslim, and Jew, met for a sacrificial feast every September to honor Noah. Modern wars and frontiers have put an end to that tradition. Gertrude's idyll ended with a presage:

We stayed [at the Ark] many hours, lunched and slept and looked at the view and breathed the delicious cold air. And at last reluctantly we came down and walked back for a long way over the tops of the hills. And here we had a little adventure. We met some Kurdish shepherds who had brought their flocks up to the top of Judi Dagh in order to avoid paying the sheep tax; and they took us for soldiers and we had to explain the true situation amidst rifle shots.

Kurds with rifles, on the lookout for Turkish soldiers. How little has changed. But now those Kurds are young men and women, often educated people from the cities, and in their back pockets they carry digital cameras:

This is Judi Dagh in the 21st century: the shrine of Nebi Nuh, the prophet Noah, identified as such in the online photo galleries of the "People's Defense Forces," the HPG, the armed force usually known as the PKK, which has been fighting the Turkish Army on these slopes since the 1980s. Nothing in its shape resembles Gertrude Bell's "Ark," for indeed this is not the same place. Bell, as she notes in her book "Amurath to Amurath," had no desire to leave the cool summit and descend the southern slopes of the mountain to visit this place. Inside, according to the PKK website, we find "Noah's grave":

Like most such artifacts it is more impressive from a distance than up close; and who would wish to go down on his knees, sift through the grains of earth, and deliver a scientific judgment on its legend's authenticity? I can see why an archaeologist would find meaning and excitement in such an endeavor. For me, the magic is in the distance; the mystery is its own reward.

And that other mountain, the Five-thousand Meter Fantasy on the Armenian border? Close up it is black rock and lava flows, useful only for tour guides, hobbyists, guerrillas, and Kurds who have flocks to graze. Me, I'm on Judi's side.

Note: This post originally appeared, in a slightly different form, at Progressive Historians.

Labels: Ararat, Cudi Dagh, Gertrude Bell, Noah's Ark