The Ferocious Past

The Ferocious Past

Dr. Grant of Kurdistan: 1807-1844

By John Agresto

Mr. Agresto, former president of St. John's College, Santa Fe, New Mexico, is currently interim provost of the new American University of Iraq-Sulaimani, in Iraqi Kurdistan. Previously he served as senior higher education advisor to the Coalition Provisional Authority in Baghdad, 2003-2004. In the fall of 2008 he will be a visiting professor at Princeton University. This article appears as the preface to the paperback edition of Gordon Taylor's Fever & Thirst: An American Doctor Amid the Tribes of Kurdistan, 1835-1844 (Academy Chicago Publishers). Previously posted at History News Network, 19 May 2008.

Everything seems so different now. From my room here in Sulaimani, in Kurdish Iraq, I can look down the street to the dilapidated green domed Shiite mosque and, from there, to the more prosperous Sunni mosque not too far behind it. Up the street is the Kurdish Cultural Center next to the Chaldean Catholic church, next to the headquarters of the Communist Party. Overlooking it all is a heavily treed compound that everyone says is the CIA headquarters. No one seems to think twice about any of this; religion, tribe, sect, nationality, politics...in this part of Kurdistan they all seem to coexist peacefully, even happily, together.

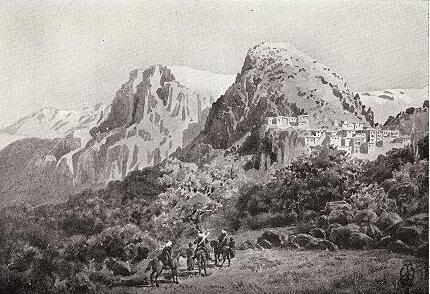

Compared to the world described in this extraordinary book, things seem different, things are different. The Kurds of Iraq, once surely one of the most ferocious people anywhere, have calmed down a good bit. Getting a job, owning a Nissan dealership, visiting Europe, flirting and being flirted with...all these are more important these days than cutting off your neighbor's ear. Commerce, trade, and money-making have worked their wonders on this part of the world, and turned peoples' attention to less sanguinary pursuits. Islam - never as fanatical here as in other parts of the Middle East - remains a mildly cohesive rather than a divisive element. And nationalism, Kurdish nationalism, exercises an attractive force that erodes, dissolves , many of the petty differences that only recently separated tribe and village and family.

Beyond politics and nationality, even the ancient religious landscape seems to have been erased by time. Asahel Grant, M.D., the great protagonist of this book, went to minister to the "Nestorians." But even among serious Christians, who these days knows anything about the Nestorians? No matter that these Christians were the offshoot of the first great and lasting divide in Christendom, dating back to 431 AD, when the Church of the East separated itself from the rest of Christianity. No matter that, for a while, these Nestorians - "Assyrians" as we refer to their remnant today --might even have been Christianity's dominant branch, with Nestorian churches thriving as far away as China, India, Japan and Tibet. But that was then, and surely times have changed.

So maybe everything is different now, and maybe Gordon Taylor's book is simply a beautifully written, impeccably researched, compellingly told historical curiosity. But... why do I have this odd feeling this book is more than that?

Perhaps, as the French might say, the more things change the more they remain the same. Look again at the Kurds. It wasn't all that long ago that half the Kurds of Iraqi Kurdistan, under the banner of the Kurdistan Democratic Party, called upon their arch-enemy, Saddam Hussein, to help them exterminate their political rivals in the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan. Not to be outdone, the PUK, in turn, called upon the hated Iranians to help them in destroying the KDP. And now, fifteen years later, a political alliance brings both parties together, based, as always, on newly-perceived shared interest. And the cycle called History rolls on. More importantly, perhaps Americans haven't changed much, either. Look at Asahel Grant -- physician, missionary, and educator - improver of the body, the soul, and the mind. Asahel Grant epitomizes everything admirable, everything naive, and everything almost incomprehensible to the rest of the world, about the American spirit.

In some ways, the Kurds of this book are unremarkable. Tribesmen warriors, with all the brutality of the unconquered world in which they live, they display all the virtues and all the many vices that are catalogued in all stories, travelogues, and histories since the start of writing. Perhaps the amazing thing about the Kurds is not the ferocious picture of them in this book, but what they seem to have become of late.

Nor, perhaps, should we be too surprised by the character of the Nestorians, even though Asahel Grant, in his most American naiveté, was initially taken aback by their un-Christian like natures. (How else to describe a sect so rife with murderers, thieves, swindlers, and extortionists?) Despite the fact that most of us would like to think otherwise, that there are serious religions and serious religious sentiment without a shred of morality is a fact of life.

No, for me at least, the most amazing thing about this more than amazing book is Asahel Grant, the American. We meet the good doctor with a swollen face, bleeding himself with a lancet. We meet him in the sixth year of his sufferings. He has already lost his wife and two infant daughters to the ravages and diseases of Kurdistan. Yet he bleeds himself, and rides on. Why? Simple answer - To bring some semblance of literacy and education, some medical relief, and some moral support to an ancient Christian denomination that civilization seems to have passed by.

But, again, why? Why should Asahel Grant care so much about people he barely knows to lose his wife, his children, his health, and ultimately his life over them? In a world these days where we so easily talk about the common threads of our humanity, how all of us are really the same, why does Asahel Grant, the American, seem so different? Why is he concerned about the health of - of all people! --Kurds? Why does he exhaust himself over the education of children not his own? Why does he care if these "Nestorians" fall under the sway of the pope or not? Why are their bodies, their minds and the freedom of their spirits of any concern to him? To be sure, not one of the people he ministers to would have given up all they possessed to cross the ocean and climb the hills to minister to Asahel Grant. So why? Why does he do it?

This is hardly an idle or academic question in my life. When I look out my window here in Kurdistan I see more than buildings. Not missionaries exactly, but I do see Americans setting up schools, starting clinics, laying sewer pipe, helping to build roads.... All with lives elsewhere, all with families left behind. Like Asahel Grant, none of them are here for money or oil or politics or honor or acclaim. What's the idea or the idealism that drives them? Is it the same vision of Humanity that drove Grant? I think it is, though I'm not sure what to call it. Nor do I fully know exactly why it's there.

Perhaps the Kurds are changed from what they were in 1840. For sure the Nestorians are pretty much gone. But Asahel Grant seems still to be around, with all his idealism, all his boundless energy, all his up-to-date technology, all his mistakes, and, all too often, all the failures that come from his misplaced good intentions. Fever and Thirst, like any great book of biography and history, is hardly a book just about the past, hardly a curiosity at all.

In saying that, I have only touched on one of the wide-ranging themes of this book. Yet, even if we resist succumbing to any of the grand and perplexing themes of the book, the fascinating thing about Fever and Thirst is that we can easily take in its hundreds, its thousands of wonderful details. "Phlebotomy"? Here it is. Ever wonder what the sweet that Kurds and Arabs call Manna from Heaven is made of? That's right...aphid secretions. (Sorry to say, I read it here after I had eaten it.) Need to know about gallnuts or mercury poisoning or the proper use of leeches? No worry; they're all here. Or perhaps you had forgotten that lions roamed Iraq until the 1920's? From philosophy to botany to politics, religion and medicine -- I now know how the first reader must have felt upon opening Diderot's Encyclopedia.